It is no secret that participating as a validator node (aka “full node”) in the Ethereum blockchain requires non-trivial hardware and storage resources. The hardware requirements to run a Geth full node (one of the more popular Ethereum full node implementations) state that the recommended minimum storage is a 2TB SSD drive - and with a default cache size, operators should expect storage to grow at a rate of about 14GB/week.

These storage requirements apply to anyone who wants to help validate transactions on the mainnet, not just to “staking” validators who want to earn Proof-of-stake rewards for validating transactions (who have additional requirements, such as ensuring high node uptime).

The more costly the hardware requirements, the fewer the number of parties capable of running a full node. Less full nodes leads to increased load on fewer servers, or to more parties relying on intermediaries (such as “node providers”) to operate the hardware for them.

This got us thinking: can we modify the block validation protocol used in networks like Ethereum so that storing the full blockchain state is no longer a prerequisite for participating as a block validator? In other words, can we let a node with “small” storage capacity (say, 5-10GB) meaningfully contribute to transaction validation without requiring it to store a full copy of the chain, and without compromising blockchain data integrity?

Today at the BRAINS 2024 conference in Berlin my PhD student Weihong Wang presented our work on “A Scalable State Sharing Protocol for Low-Resource Validator Nodes in Blockchain Networks” which addresses this question.

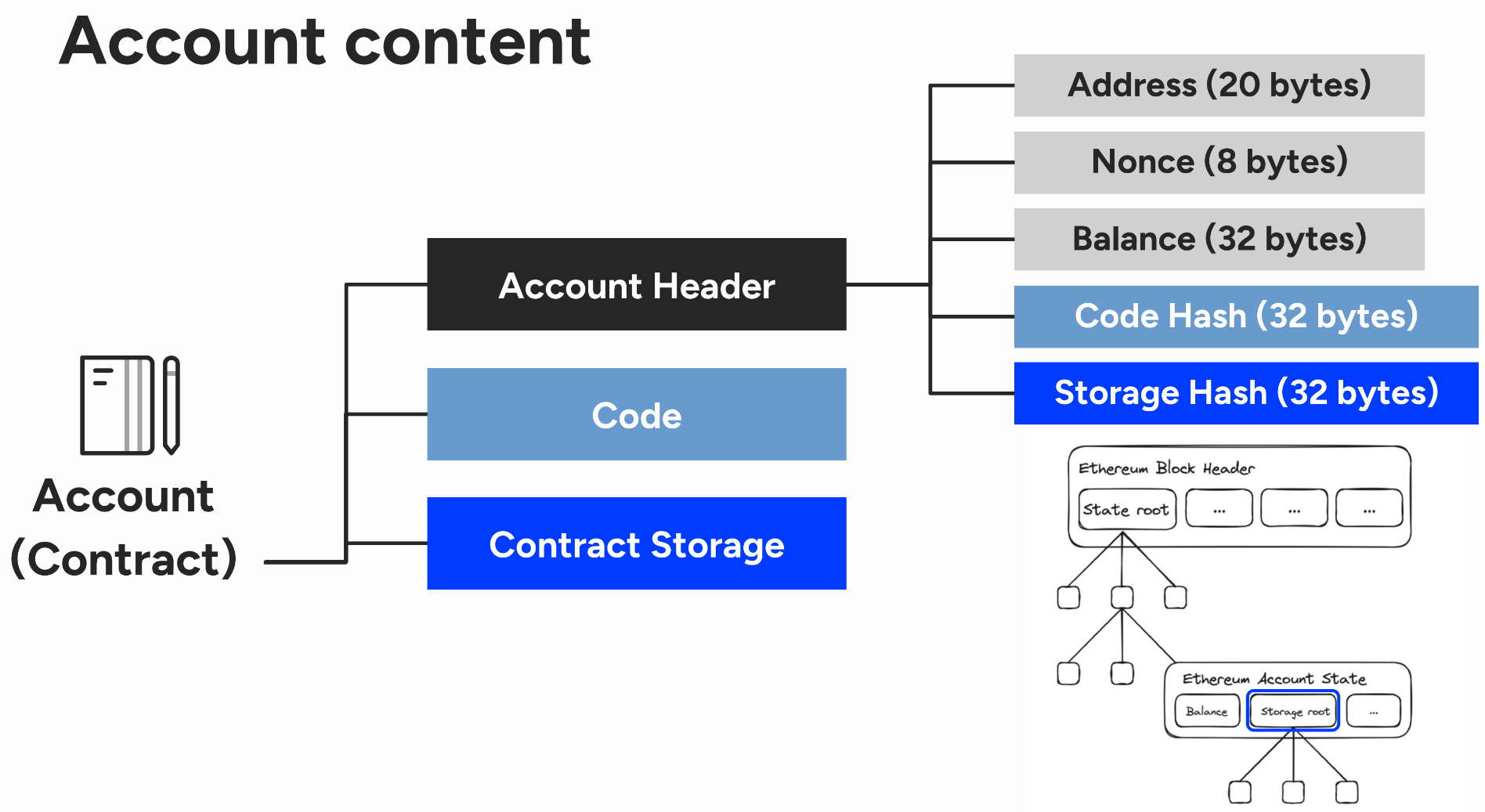

You can think of Ethereum as a virtual computer whose memory stores the “state” of many thousands of individual “accounts”. Each account is identified by a 160-bit address (0x...), and a variable amount of storage (which, for smart contract accounts, includes the contract’s code and state storage). The key idea explored in our paper is to take a cue from decentralized storage networks and distributed hash tables (DHTs), most notably Kademlia, to distribute storage of all this Ethereum account state across many nodes, using the account address as the key to efficiently retrieve the associated data.

Each node in our adapted validation protocol can choose how much storage it wishes to contribute to the network. We call nodes that do not store the full Ethereum account state “low-resource nodes”. A low-resource node can participate in block validation just like a regular full node, but as part of the validation logic it will fetch any account state needed to validate a transaction on-demand from other low-resource nodes. We leverage Kademlia’s fast network lookup (logarithmic in the number of network peers) to efficiently locate peers that store a copy of the relevant account state, and we leverage Merkle proofs to ensure data integrity (which Ethereum makes possible because it stores all of the account state in a giant Merkle-Patricia Tree, and includes the root hash of the tree in the block header). To verify the proofs we assume that low-resource nodes have access to the block headers from the authoritative chain through Ethereum’s consensus committee, just like regular full nodes do.

Our modified validation protocol effectively trades off storage space for increased block validation latency and increased bandwidth needs to fetch remote storage state. The effectiveness of our approach heavily depends on the data access patterns of Ethereum transactions. It’s obvious that if only a small fraction of accounts is actively queried or updated in the majority of block transactions, then caching the most frequently accessed account state would be a very effective strategy to avoid too much fetching of remote account state, thus keeping latency and bandwidth overheads low. The paper therefore starts with an extensive quantitative analysis of data access patterns (and account storage needs) in Ethereum, based on real-world transaction data from the Ethereum mainnet. Our findings show that there is significant data locality to exploit in real-world Ethereum transactions, making the protocol potentially feasible in practice.

On simulated transaction data, we show that a network of low-resource nodes can achieve up to 98% storage reduction compared to a network where all nodes store a full copy of the data, at the expense of an additional bandwidth cost of 319 to 1065 GB per month, while keeping block validation times within the 12-second block generation interval. One surprising finding (at least to me) was how much the size of the merkle proofs contributes to the total amount of data that needs to be fetched from remote nodes (in order to validate the data integrity). Merkle proofs are critical to ensure data fetched from untrusted peers is consistent with the latest valid “world state” of the Ethereum computer. In many cases, the size of the merkle proof can be 10 to 50 times larger than the tiny amount of account storage state that it helps validate! We therefore also studied the potential savings of switching to Verkle trees, which allow for much more compact proof sizes. Our findings show that switching to Verkle trees can reduce the bandwidth cost of our protocol by a factor of 2-3x.

As they say, “the proof of the pudding is in the eating”, and an important next step would be to actually implement this protocol as an adaptation of, say, a Geth client, so that we can actually try the approach and validate it under real-world conditions on a test-net. Another important area of improvement is to study data availability guarantees when data is no longer stored by all of the nodes.

The quantitative analysis, the design of the protocol, and the validation of the protocol on simulated transaction data was all carried out by my thesis student Ruben Hias, who did this work as part of his Masters thesis project, with mentoring by my PhD students Weihong Wang and Jan Vanhoof. Ruben did outstanding work analyzing the problem, coming up with a proof-of-concept state sharing protocol and setting up simulation experiments to validate the feasibility of the protocol. For the experiments with Verkle trees, he interacted with Ethereum Foundation researchers, who were interested to learn the impact on storage needs by switching to Verkle trees, as this not only benefits our protocol, but also light clients. Verkle trees are on the roadmap to be integrated into Ethereum.

A pre-print author-copy of our paper is available on Arxiv. A copy of Weihong’s presentation slides for the paper presentation at BRAINS’24 is here.