Membranes are a defensive programming pattern used to intermediate between sub-components of an application. The pattern is applicable in any memory-safe programming language, and I explain elsewhere on this blog how they work in JavaScript.

The pattern has been around for many years, but is not widely known. My aim in this article is to lay out the general ideas behind membranes. Because most of my experience with membranes has been built up in the context of Web standards, I will mostly be covering this from the angle of JavaScript and Web platform-related use cases. Remember though that the membrane pattern is more widely applicable and not in any specific way tied to the Web.

Historical note: membranes originate from research on capability-secure systems, going back at least to early capability-secure operating systems such as KeyKOS and capability-secure languages such as Joule and E. The pattern as presented in this article is mostly based on the description in Mark S. Miller’s PhD thesis on robust composition. The membrane pattern has been independently discovered and applied in the functional programming community to implement contracts for higher-order functions.

Isolating applications versus application sub-components

Operating systems commonly employ a variety of protection mechanisms to coordinate the interaction between applications. Processes, for example, introduce distinct address spaces to isolate applications from each other.

Membranes are a secure programming pattern that achieve a similar kind of isolation, but within a single application rather than between different applications. The name “membrane” is meant to evoke an association with cell membranes, which protect delicate internals from a chaotic external environment while still enabling regulated interaction with that environment.

A membrane allows a coordinator to execute some logic in between every interaction with a particular sub-component (which may contain untrusted third-party code). A host webpage might want to protect itself from an embedded script. A browser might want to isolate a third-party browser extension (plug-in). A web framework might want to track and observe mutations in the objects of its web app to refresh the UI.

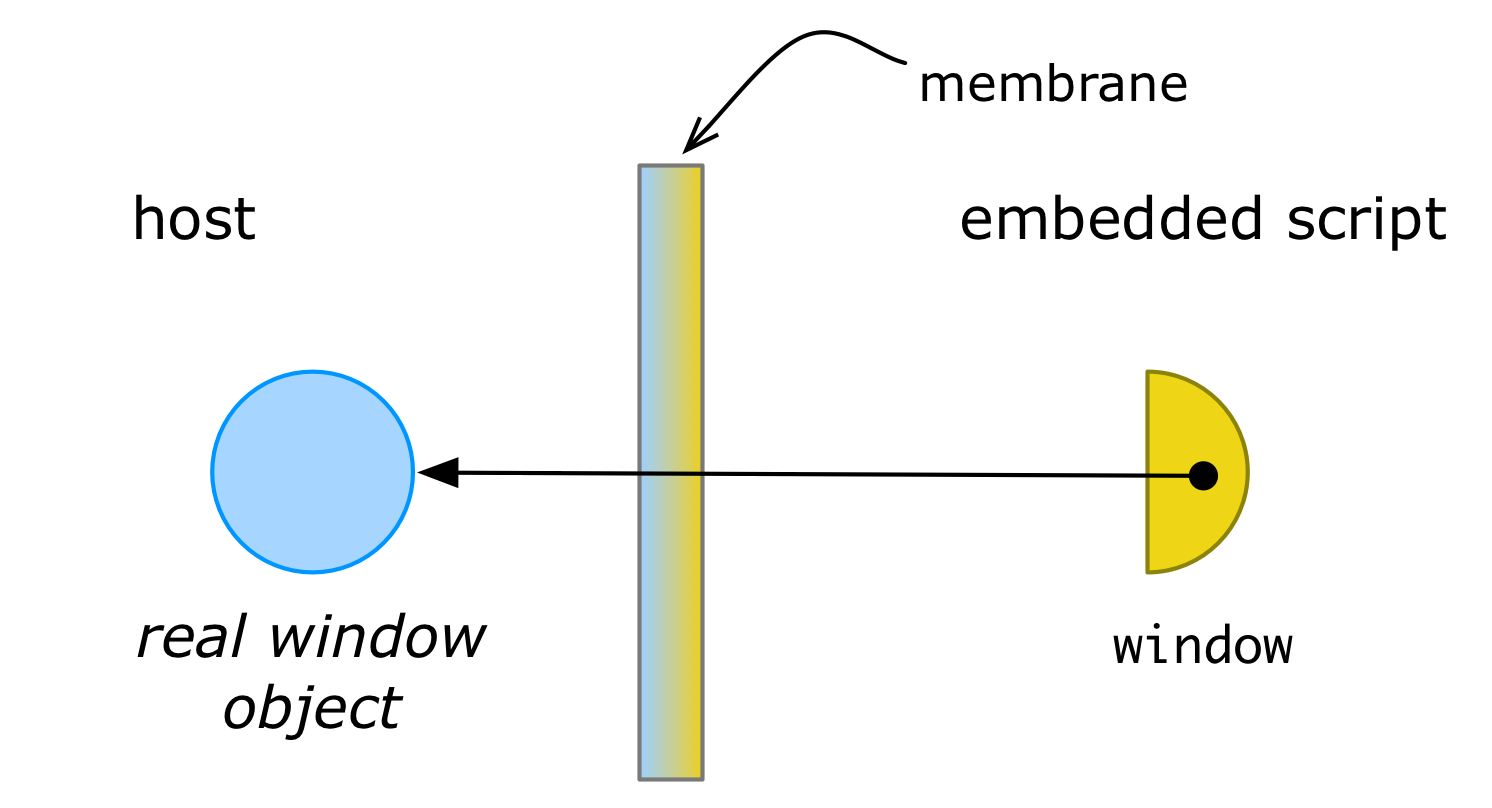

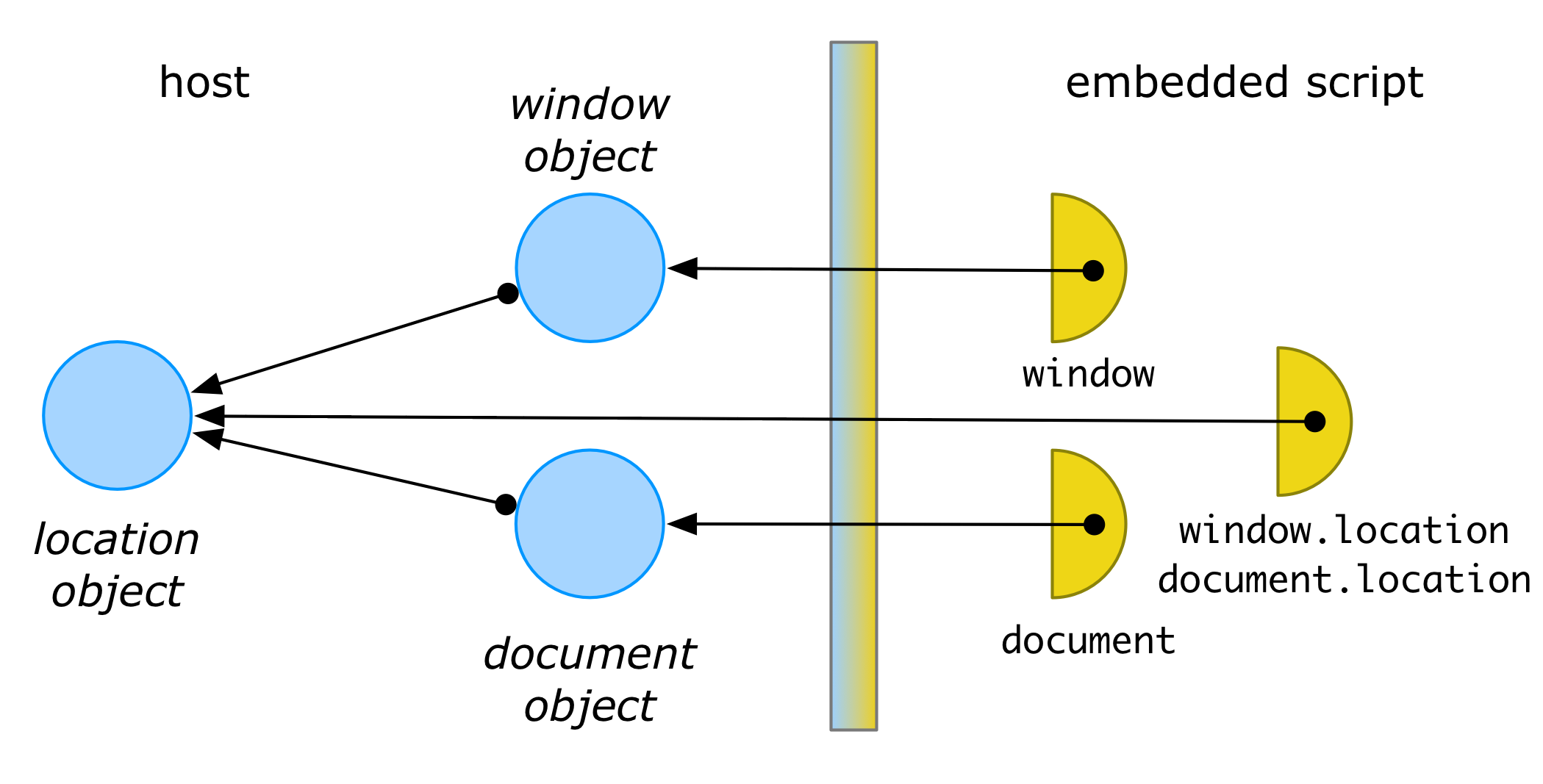

A membrane is a controlled perimeter around one or more objects and is usually implemented through proxies or “wrapper” objects. In a typical membrane setup, the perimeter starts with a single root object. For example, code inside a web page might wrap its window object in a membrane proxy. The proxied window could then be passed on to an embedded third-party script:

In the above figure, the half-circle represents a proxy object providing access to some resource (object) in another sub-component.

Properties of a membrane

Let’s briefly go over the key properties of a typical membrane pattern.

Membranes are transparent and mostly preserve behavior

Membrane proxies are usually designed to be transparent. That is: to a client of the proxy, interacting with the membrane proxy appears indistinguishable from interacting with the object it wraps. This is important, because client code that expected a real object will still work when it is passed a proxy instead. In the example of the third-party script that receives a proxied window, the script is likely unaware that it received a proxied window, and will use the proxied window as if it were the real window object.

Note that I wrote “the membrane proxy appears indistinguishable”: the creator of the membrane usually wants to execute some logic when the third-party code interacts with the wrapped object. This logic usually implements some kind of “distortion” on the wrapped object. In our web page example, the host page might have replaced some operations of the real window with less sensitive dummy operations, for example querying the window for its history could just return fake history data. A more sophisticated example could be a membrane that wraps a <div> DOM element in the host page into a virtual window object, such that a third-party script can only render content inside that <div> without affecting the rest of the webpage.

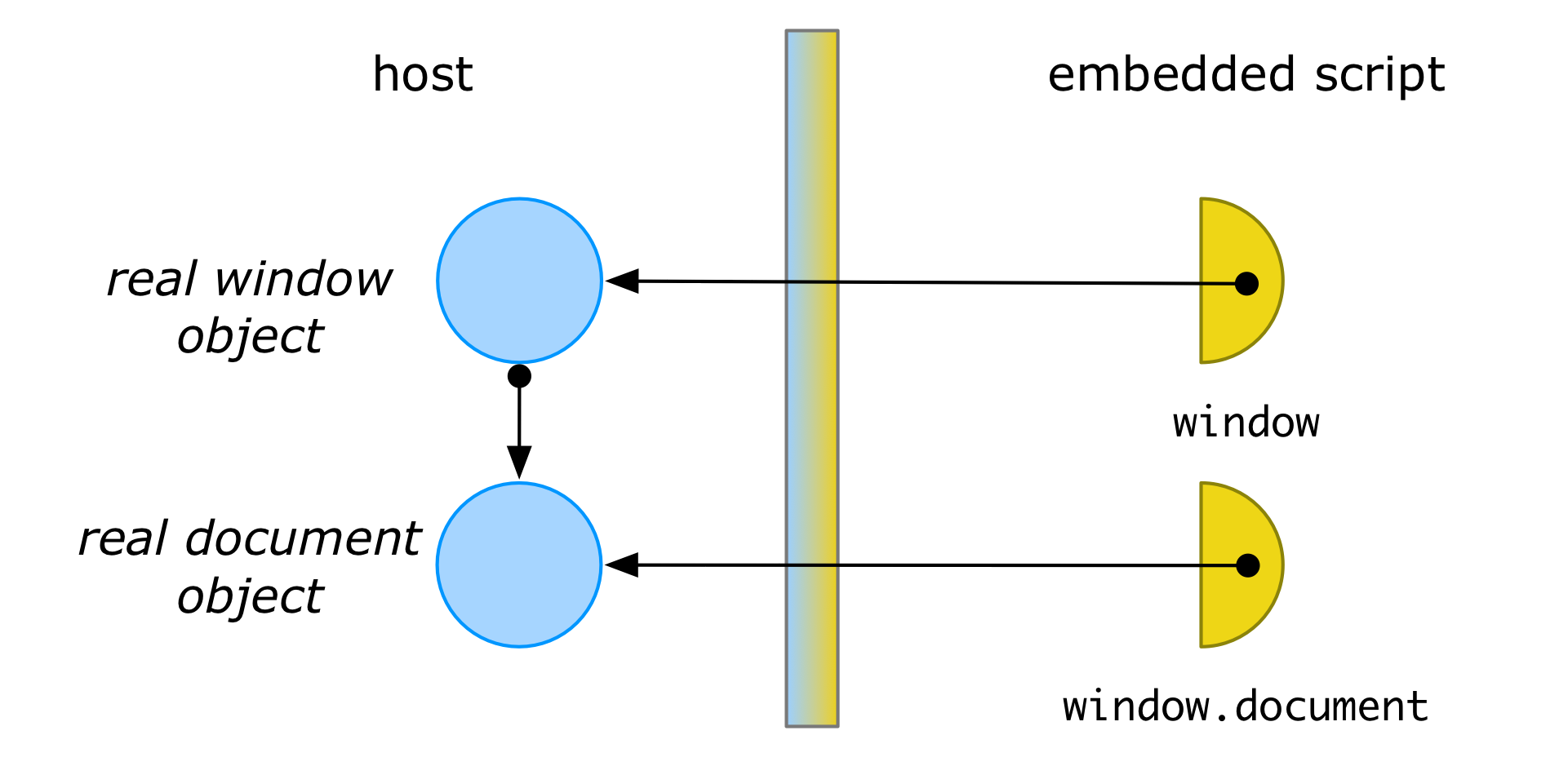

Membrane interposition is transitive

Using proxy objects as wrappers for other objects is a very common design pattern in object-oriented languages. So what makes a membrane different from a traditional proxy design pattern? The defining feature of a membrane is that any object that gets passed through a membrane proxy gets transitively wrapped inside another membrane proxy (usually enforcing the same logic as the original). For example, if window is the proxied window, then window.document will return a proxied Document object.

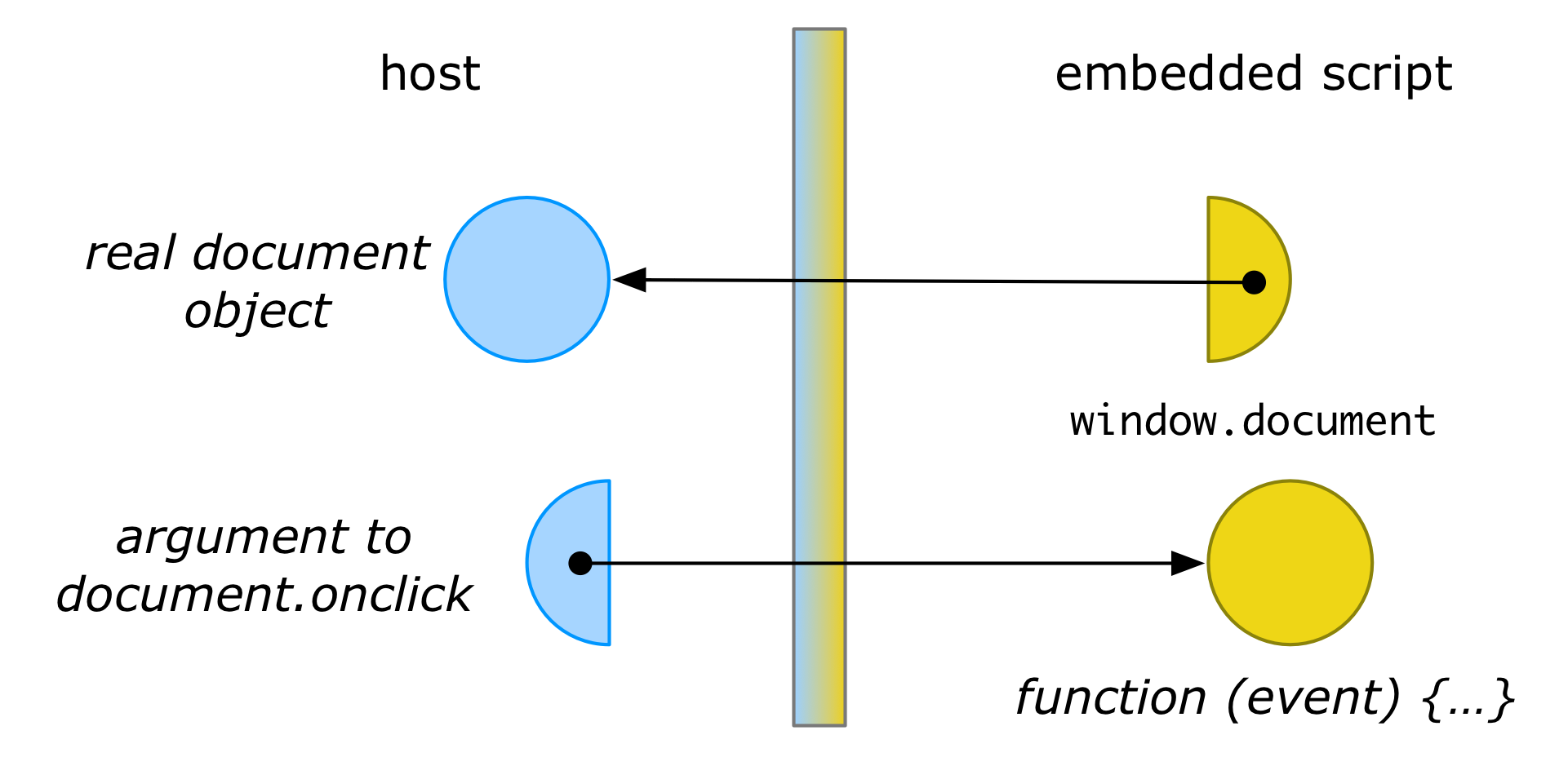

Often we don’t just want to isolate the third-party code from the host, but also isolate the host from the third-party code. A membrane can accomodate this by wrapping the arguments passed to methods on a membraned object:

window.document.onclick = function (event) {

console.log(event.target)

}Here, the function object passed to onclick would be wrapped in another membrane proxy:

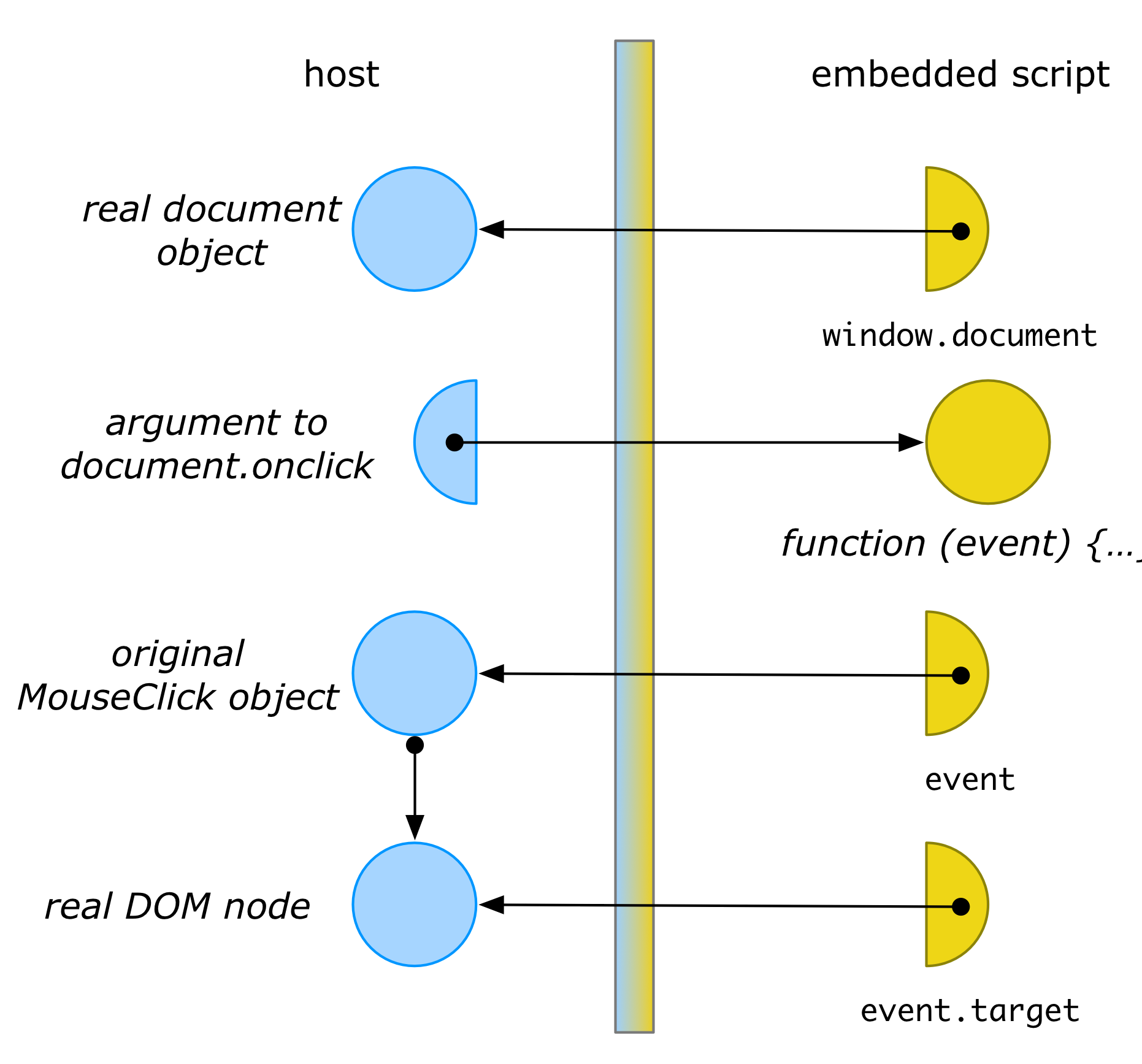

This wrapping ensures that, if code in the host later calls back on the function with some event e, the membrane can ensure a proxy to e is passed instead. Thus, the event parameter to the callback would be a wrapped MouseEvent object. The membrane can thus continue to interpose its logic to uphold its distortion. For instance, it can ensure that event.target returns a properly wrapped DOM node, rather than the real DOM node (from which the original document could be retrieved).

The fact that a membrane “grows” itself through transitive interposition is extremely powerful and useful, because it means the security perimeter around a set of objects is flexible and dynamic. There is no need to list all objects to be wrapped upfront. This transitive wrapping also allows membranes to deal with complex (“higher-order”) object-oriented or functional interfaces, where objects or functions are routinely parameter-passed as values to other objects or functions, supporting dynamic data flows that cannot be statically predicted.

Membranes preserve identity

Many programming languages have mutable data types, such as objects or records with mutable fields. Mutable values have identity. For example, in most object-oriented languages, objects have identity, and this identity can be directly observed through identity-equality operators like == in Java or === in JavaScript.

In such languages we usually want a membrane to preserve identity of values across the different sides of the membrane. Continuing our web platform example, if window is a membrane’d window object and location is a membrane’d location object, then we still like invariants such as window.location === document.location to hold on either side of the membrane:

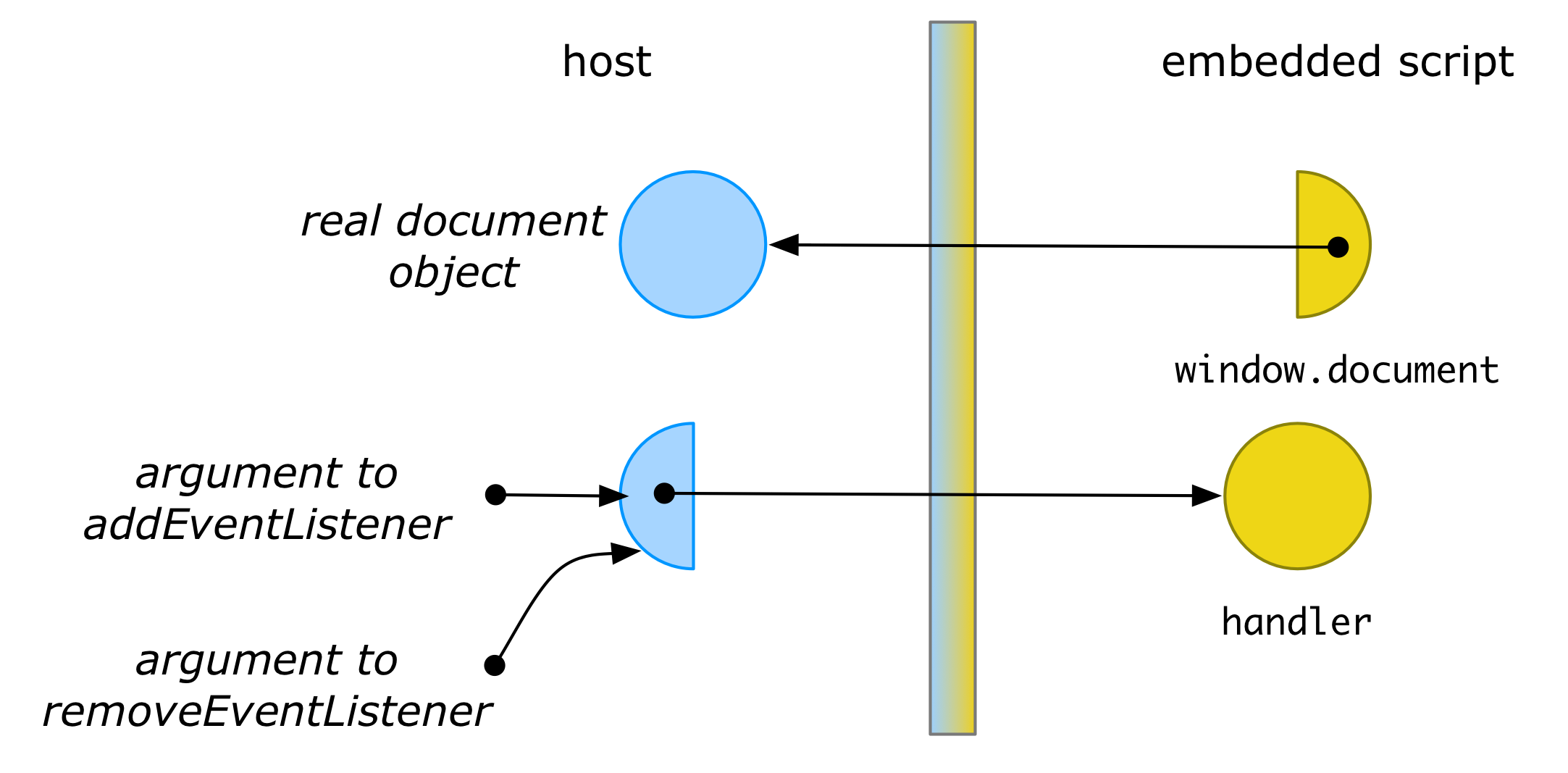

We would also like values that cross the membrane multiple times to retain their identity on the other side of the membrane. To see why this is important, consider the example of registering and later unregistering an event handler through a membrane’d document:

let handler = function(event) {

console.log(event)

}

document.addEventListener("click", handler, true);

// sometime later...

document.removeEventListener("click", handler, true);

In order for removeEventListener to find and unregister the function installed by addEventListener, the argument passed to both functions should be identical, otherwise the original handler function would never be found.

Finally, we usually want a wrapped value that is passed from one side of the membrane to the other, and then back again, to be replaced by its original value. To see why, consider the simple identity function:

function identity(x) {

return x;

}Let’s assume this function gets exposed through a membrane as a wrapped function named id. Then, on the other side of the membrane, for any value v, we would like id(v) === v to hold. This can only be the case if membrane wraps v when passing it as an argument to id and then unwraps it again when passing it as the return value back to the client.

Preserving identity usually requires membrane implementations to use caches to ensure that they only allocate a single canonical wrapper for every stateful value. To make sure these caches don’t leak memory, implementations would use data structures like a WeakHashMap in Java or a WeakMap in JavaScript. These maps hold only weak references to their keys and so do not prevent the objects from being garbage collected.

Strengths and limitations

To really be effective in isolating application sub-components, it is crucial for a membrane to intercept all possible interactions between objects of the sub-components it is trying to isolate. In particular this requires the complete absence of mutable state that is globally visible across sub-components. In languages like JavaScript, this usually requires making sure the global environment is either made immutable or virtualized as well (see Secure ECMAScript for a principled attempt to do this). In languages like Java, this usually requires avoiding static fields or dangerous APIs (see Joe-E for a subset of Java that enforces such properties).

One advantage of using membranes to isolate different parts of an application is that the objects on different sides of the membrane still reside in the same address space, and so can still communicate through standard programming abstractions such as method calls or field accesses. They can also share direct pointers to (usually immutable) shared state. This is very different from isolation through process-like abstractions, which introduce separate address spaces. This usually forces the use of inter-process communication (IPC) mechanisms, and usually requires redesigning the APIs of the sub-components of the application. For example, in browsers, another way of isolating different parts of a web application is through Web Workers, which can only interact by asynchronous message passing.

Because membranes operate within a single application’s process and address space, they do not protect against denial-of-service attacks or crashes of the isolated sub-components.

Membranes in the wild

Let’s review a few real-world examples of the membrane pattern.

Script compartments in Firefox

Perhaps one of the most widely deployed uses of membranes is inside the Firefox browser. Firefox’s script security architecture follows the membrane pattern to implement security boundaries between different site origins and privileged JavaScript code. The membrane pattern actually helped to mitigate multiple high-severity security bugs.

Membranes in Firefox are called cross compartment wrappers.

Script sandboxing with Caja

My running example of a host webpage trying to protect itself from an embedded script is one of the primary use cases of Google Caja. Caja enables the safe embedding of third-party active content inside web pages and has been used to protect various Google products including Google Sites, Google Apps Scripts and Google Earth Engine.

Custom DOM views with es-membrane

As a spin-off on working on the Verbosio XML editor Alexander J. Vincent created a reusable membrane library for JavaScript. His original use case was to coordinate different Firefox add-ons, enabling each add-on to have a custom view of the same DOM. For instance, each add-on could define its own “expando” properties on a shared DOM.

The es-membrane library was also the first to generalize a typical two-party membrane, as discussed above, into an N-party membrane where a coordinator can directly intermediate between multiple sub-components without having to create multiple membranes.

Observing mutations with observable-membrane

While membranes were originally proposed as a defensive programming abstraction to isolate sub-components, the membrane pattern can be used for other purposes beyond enforcing some security property. For example, Caridy Patiño and team at Salesforce have successfully used the membrane pattern to observe mutation on an object graph. Their implementation is publicly available.

One reason one would want to observe mutations on an object graph is to enable data-binding in a web application framework: the web framework observes the object graph of its web application, and mutations require the web framework to refresh the UI. This example code shows how to build reactive web components using this pattern.

Figma plug-ins

Note: this section was added in March 2025, long after publication of the original blog post in 2018.

The Figma team used the membrane pattern to safely embed plug-ins into their main product in such a way that the plug-ins could run on the main thread, with synchronous API access to the Figma document. Membranes were used to ensure that JavaScript values from the surrounding Figma webpage are properly converted into JavaScript values for a small, embedded JavaScript VM.

Their engineering blog post actually is a great read on the considerations that go into running untrusted JavaScript code alongside your main application, and the various techniques one might use, along with the trade-offs involved.

What experience tells us

We highlighted earlier how it is usually important for membranes to be transparent. Indeed, what experience seems to tell us is that membranes work best when their distortion logic does not attempt to change the actual values that get exchanged across the membrane but instead implements a kind of filter on data or a fail-stop behavior on control flow.

Examples include:

- Whitelisting: only expose a subset of data or behavior to sub-components.

- Expandos: treat new properties added by one sub-component as virtual properties that are invisible to other sub-components.

- Revocation: install a kill-switch on a membrane that can instantly turn all membrane proxies into safe dangling pointers (any use of a membrane proxy after access was revoked will trigger an exception). This was the original inspiration for membranes in Miller’s thesis. Here is an example implementation of such a “revocable membrane”.

- Contracts: assert pre- and post-conditions on method arguments and return values. Because the membrane can track the flow of data values, when an assertion fails, the membrane knows how to assign “blame” to the offending sub-component that passed or returned a faulty value. See contracts in Racket as a concrete example of this pattern.

- Logging: log all interactions with a sub-component without otherwise altering them, for debugging or auditing purposes.

“Wrapping” up (pun intended)

Membranes are a defensive programming abstraction to isolate or intermediate between sub-components within a single application. They are usually implemented by creating a dynamically growing “distortion field” around objects by transitively wrapping each object in a protective proxy object.

Implementing a membrane correctly is not easy. For example, in JavaScript, due to the complexity of the language there are many ways for objects to interact (just look at the number of traps in the Proxy API). Luckily libraries like es-membrane and observable-membrane are starting to make things easier by offering membranes as an abstraction, letting you plug-in your “distortion logic” and letting the libraries take care of most of the implementation details.

If you want to dig deeper into membranes in JavaScript, you may be interested in these other articles on my blog: